Authors

Jonathan Marc Berlingeri1, Matthew Chartrand2, Elson Shields2

1 — Department of Animal Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

2 — Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Recent legislation introduced by Governor Cuomo has focused on re-introducing industrial hemp production in New York State (NYS). In 2018 New York State’s Ag and Markets Pilot Program approved over 130 farms to produce industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for fiber, grain, cannabidiol and dual-purposes. Prior to NYS Industrial Hemp Pilot Program there was a total absence of cultivated hemp acreage in the state since the end of the second world war. There are remaining small pockets of wild hemp on abandoned farmland throughout NYS, remnants of hemp production for rope needed during the second world war.

Currently, insect pest pressure in cultivated hemp is very low, due in part from the long time period where hemp was not commercially cultivated. At this point, it is unknown if and when any pest species will become numerous enough to require management.

Effective pest management starts with the correct identification of insects in the field and the ability to tell the difference between pest insects, their damage and the beneficial insects which assist the farmer with pest control. To prepare for the potential resurgence in pest pressures NYS hemp farmers should develop a solid understanding of the life cycle and phenology of pests that threaten their crop, the degree of damage each species poses, and the current options in non-agrochemical control methods (cultural and biological). This page has been developed in order to provide NYS Industrial Hemp farmers with essential knowledge of the pests, beneficial insects, and pollinators they might encounter in their fields during the growing season.

Tarnished Plant Bug, Lygus lineolaris L.

Time for concern: June through September

Characteristics and life cycle: Tarnished Plant Bug (Lygus lineolaris) or TPB is a common pest that has been found abundantly throughout NYS hemp fields. Adult TPB is a brown insect with mottled shades of reddish-brown and yellow-brown. The adult is about 1/4 inch long and oval-shaped. The nymphs or immature forms have long legs, antennae, and piercing-sucking mouthparts. Unlike aphids and some other sucking pests, TPB will destroy cells and feed on the liquid that is produced causing more severe injury to crops. Nymphs are the most destructive phase of this insect. They grow rapidly and feed constantly, gradually taking on the appearance of the adult. Their life cycle is completed in about 3 weeks. There are multiple generations per year.

Damage: Likely to be minimal. TPB feed on younger tissues and may cause flower abortion, and deformities of seeds. Distortion in flower formation is also a key characteristic of TPB damage. Hemp grown for CBD, grain or as an oil seed is more susceptible to TPB damage than fiber varieties as TPB damage can reduce the number of flowers, seed production and seed quality.

Control: Tarnished Plant Bug has a number of natural enemies that provide a means to reduce TPB populations; Big-eyed bug (Geocoris punctipes), Brachonid wasps (Peristenus digoneutis, Peristenus pallipes, Leiophron uniformis), Mymarid wasp (Anaphes ovijentatus). In order to encourage parasitism and predation of TPB please refer to the Michgan State Universities guide to native plants and ecosystem services and to ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping. Hemp grown adjacent to alfalfa or vetch fields will likely contain greater numbers of TPB and migrations into hemp fields will likely increase following the drying or harvesting of these crops. In addition, the hemp fields adjacent to alfalfa or vetch will be susceptible to larger infestations of natural enemies after the neighboring crop is harvested or by simple insect movement. No chemical control is currently available for TPB in NYS hemp, nor is it necessary in most cases.

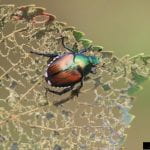

Japanese Beetle, Popillia japonica L.

Time for Concern: Larvae: May through early June. Adults: June through August.

Characteristics and Life Cycle: The Japanese beetle is about ½ inch long with a shiny metallic green head and thorax and iridescent coppery brown wing covers. The larvae, or grubs, have translucent light grey and white coloring with a brownish head, and are about ½ inch long with three pairs of legs on the forepart of the body. The grubs rest in a C-shaped or curled position and feed on roots of grasses and are a serious pest in turf systems.

Damage: Larvae: Minor to Severe root damage. Japanese beetle’s larval stage is the most damaging in its life cycle due to root feeding early in the season potentially crippling growth and causing poor stand. However, larval damage is a rotational threat when hemp is following a grassy field the previous year (rotated pasture, grassy alfalfa, grassy corn field). In the case of rotated fields with lots of grass, there is also a threat of native white grubs/June beetle and wireworms on the emerging and small plants. Adults: Minor to Moderate defoliation. Adult Japanese beetles are a potentially significant defoliator and also feed on hemp flowers (WC, 2019). Although potentially damaging, no significant cases have been reported in NYS. Japanese beetles are social insects and tend to feed in groups using pheromones to signal the presence of food to other adults, the adults are the potentially damaging life stage in hemp. Japanese beetles do not consume leaves in their entirety, they tend to feed on the areas between leaf veins creating the characteristic skeletonized leaves indicated in the above image.

Control: Current recommendations for biological control of Japanese beetle are limited as the adult beetles lack natural enemies aside from birds. Japanese beetle traps are available for purchase but should not be used in hemp fields as they may increase the number of beetles in a particular area and are better used on the outer perimeter of the field if at all. Japanese beetle will tend to be present in higher numbers in hemp fields adjacent to large areas of turf.

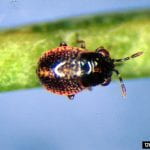

Flea Beetle, Phyllotreta spp.

Time for Concern: April through July

Characteristics and Life Cycle: Flea beetles are shiny and black, about 1/16 inch long, and have large hind legs which they use to jump when disturbed. Flea beetles overwinter as adults in leaf litter and vegetation and can infest fields quickly in early spring. Eggs are laid in the soil near the plants and the larvae feed on the roots causing minor damage. A second generation of adults emerges in late July or early August and after feeding migrate out of the field to overwinter in protected spaces.

Damage: Likely to be minimal. Only very minor flea beetle damage has been reported in the scientific literature (WC, 2019). Flea beetles chew tiny holes, often described as “shotholes”, through foliage. Flea beetles can cause damage during the seedling stage by feeding on cotyledons, which may reduce stand in direct-seeded hemp. The threat of flea beetles damage concludes after hemp has developed several sets of true leaves. At this point, the plant can tolerate the minor damages caused by the beetle.

Control: Biological control agents are commercially available although in most cases are not a necessity. Entomopathogenic nematodes (Sternernema feltiae L.) have shown promise in reducing flea beetle larvae in canola and are available for purchase as a sprayable polymer gel as well as in forms suitable for soil application (Antwi et al., 201). Entomopathogenic fungi (Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium brunneum) have also shown to be effective at reducing leaf injury and improving yield in canola but products containing these fungi have not been labeled in NYS. Microcotonus vittatae Muesebeck, a native braconid wasp, parasitizes and kills the adult flea beetle. In order to encourage native enemies of flea beetle and other beneficials to visit your hemp please refer to the Michgan State University’s guide to native plants and ecosystem services and to ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping.

European Corn Borer, Ostrinia nubilalis

Time for Concern: May through September

Characteristics and Life Cycle: As the name declares this insect is often found infesting corn fields but also has a variety of other suitable hosts including snap bean and several ornamentals. European Corn Borer (ECB) overwinters as mature larvae in the host plant’s stem. Hemp has been reported as one of these insect’s evolutionary hosts. Since hemp has served as a historical habitat for ECB there is some concern about the resurgence of ECB pest pressure in NYS hemp. The larvae are white to gray with a dark brown head and are 3/4 to 1 inch long when fully grown. In the spring, the larvae pupate into a yellowish to reddish-brown moths and emerge from the plant stalk where it overwintered. Adults moths mate in grassy areas around the parameter of the field and reenter the field to lay eggs. Eggs are typically laid on the underside of leaves. Newly hatched larvae feed for a short period on the leaves before migrating to the stems/stalks, leaf axials, and fruit where they bore into and enter. After feeding, mature larvae pupate in place and emerge for the second generation in mid-August.

Damage: Potentially severe. During the peak period of US hemp production, within the Midwestern states in the 1940s, European corn borer was the insect mentioned as being most often observed to damage the crop (WC, ECB). Damage to stems is evidenced by the presence of sawdust-like material and broken stems. The tunneling feeding habit of the larvae compromises the structural integrity of hemp stalks and can cause stem breakage, lodging, resulting in severely reduced yields. Currently, ECB populations in NYS are very low due to the widespread planting of genetically modified corn which has an ECB-Bt toxin incorporated into the plant. Hemp fields planted in close proximity to commercial corn fields containing these genetically modified corn varieties benefit from the ECB pest suppression provided by the modified corn.

Control: ECB has a number of natural enemies and biological control options including predatory lady beetles, minute pirate bugs and lacewings, and fly and wasp parasitoids. The release of tricogramma wasps (Trichogramma ostriniae) was found to provide comparable control of ECB when compared with commercially available insecticides in sweet corn (ecommons). Hemp fields adjacent to pepper or sweet corn fields will likely have increased ECB pest pressure. Eliminating weeds from the periphery of hemp fields is may reduce ECB numbers as they serve as breeding sites. Tricogramma wasps are available for purchase at ipmlabs.com. In addition, spray formulations of Bt have just been cleared for use in NYS Hemp. However, this material is only effective on the newly hatched larvae during the leaf-feeding stage and before they enter the stems/stalks.

Corn Earworm, Helicoverpa zea

Time of Concern: Mid-July through September

Characteristics and Life Cycle: Corn Earworm (CEW) cannot overwinter in NYS due to the winter temperatures. Instead, it migrates into NY on the warm southern winds from overwintering areas in the southern US. Depending on the date of arrival in NYS, CEW will cycle through 1-2 generations on a wide range of host plants. Each lifecycle requires about 30 days. Late summer emerged adults migrate back to the southern latitudes for overwintering survival. Eggs are deposited singly, and the emerging larvae are the damaging stage of the pest. The larvae vary in color, with green, brown, or pink stripes and a tan head. Skin is rough with characteristic short microspines that can be seen with magnification. Full-grown larvae are about 3/4 inch in length. The adult form is a moth with a wingspan of about one inch and ranges in color from tan to brown with some yellowish hues. Forewings have two darkened spots.

Damage: Potentially severe. The larvae are most damaging to hemp by tunneling into maturing flower buds and developing seeds. Injury is greatest on cannabidiol cultivars where large flower buds are produced” (WC, 2019). There have been some cases of serious economic injury reported in CBD varieties in Colorado and gran hemp in North Carolina (WC, 2019). CEW becomes attracted to hemp after it begins flowering in late summer. During this time corn — the favored host — reaches a level of maturity where the adult CEW finds it unsuitable for egg-laying. At this point, hemp may become one of the most attractive hosts. CEW feeding can cause abscission of floral buds, bud rot, deformities in seed and flower, and result in decreased yields.

Control: CEW has an abundance of natural enemies and some biological control options including predatory lady beetles, minute pirate bugs and lacewings, and fly and wasp parasitoids (NYS IPM). Hemp fields adjacent to sweet corn, lettuce, and alfalfa fields may have increased ECB pest pressure. Vetch, tomato, oats, and various weedy species including purslane, common mallow, morning glory, lambsquarters, ragweed, and velvetleaf also serve as hosts. Eliminating weeds from the periphery of hemp fields may reduce CEW numbers as they serve as breeding sites. Pheromone traps are available for monitoring CEW arrivals and activity and can be used in conjunction with developmental stages where hemp is a desirable host to time releases of tricogramma wasps to parasitize egg. The NYS sweet corn pheromone trap network can be used to monitor CEW arrivals in neighboring areas, as it is updated weekly throughout the growing season. Tricogramma wasps are available at ipmlabs.com.

Onion Thrips, Thrips tabaci

Time of Concern: Mid-July through September

Characteristics and Life Cycle: Onion thrips are 1/16 inch in length and can be brown, yellow, or white in color. Thrips lay their eggs directly into plant tissues. Eggs will hatch after about 2-3 days and the larvae will begin feeding on the surface of foliage. The duration of onion thrips’ life cycle is dependent on temperature. Under normal growing conditions, this would take about 2-3 weeks. Numerous generations may be produced annually.

Damage: Likely to be minimal. Thrips feed on the surface cells of leaves by piercing and sucking out cell contents. This results in small light-colored areas on foliage, creating a speckled appearance.

Control: Thrips have an abundance of natural predators that help maintain low populations in outdoor crops. Thrips can reach larger population sizes in greenhouses, but it is still unlikely that they pose to cause any measurable losses. Control of thrips in the outdoor setting can be achieved by encouraging natural predation through management practices described in Michigan State University’s guide to native plants and ecosystem services and in ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping. Indoor infestations can be managed with the release of predatory mites N. cucumeris and A. swirskii which are commercially available at ipmlabs.com.

Insect Pollinators in New York State Industrial Hemp

Insect pollinators are integral to U.S. food production and food security contributing more than $24 billion to the U.S. economy (White House, 2016). In recent decades substantial reductions in the number of honey bee colonies have been caused by the collected deleterious effects of predatory mites, disease, viral agents, poor management, habitat fragmentation, loss of genetic diversity, and exposure to certain pesticides. Colony collapse disorder or CCD, a rapid deterioration of bee colonies, has contributed significantly to decreases in bee colonies throughout the U.S. New York State beekeepers experienced about a 50% loss in colonies in 2015 and 2016 (DEC). The scarcity of nutritional resources during periods of floral dearth, inherently a part of monoculture systems, contributes to the susceptibility of pollinators and to the aforementioned deleterious agents.

Hemp stands to contribute to NYS pollinator health by contributing pollen, a source of lipids and protein for many pollinators. Not all varieties of hemp are pollen-producing, therefore the type of hemp grown will drastically influence the presence of pollinators. CBD hemp producers will purchase feminized seed and/or will purge male hemp plants from their fields thereby removing pollen. Although this process limits the ecosystem service that hemp can provide, it also allows for high yields of CBD to be attained from female hemp flowers. On the other hand, hemp grown for grain, fiber, and dual-purpose (grain and fiber) will produce large quantities of pollen in late summer and early fall providing sustenance to a variety of pollinators. The unique timing of pollen production in hemp provides nutritious pollen during a period of resource scarcity for pollinators. Further, certain traits in pollen-producing hemp were found to contribute to a larger diversity of pollinator visitors. Taller varieties of pollen-producing hemp attracted a broader diversity of bee species (Flicker N., Poveda K., Garb H., 2019).

Honey Bee, Apis mellifera

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) have been found throughout NYS hemp in high numbers. They visit hemp flowers to collect pollen as the plant does not produce floral nectars which are also attractive and used to produce honey. Hemp pollen can be a vital nutritional resource for honey bees and may contribute to sustaining declining honey bee populations. This is particularly valuable considering that honey bees contribute about $15 billion to the U.S. economy in their products and ecosystem services (White House, 2016).

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Bumble Bee, Bombus impatiens

Bumble bees (Bombus impatiens) have also been found throughout NYS hemp in high numbers and also visit hemp flowers to collect pollen. Hemp pollen can be a vital nutritional resource for bumble bees and may contribute to sustaining the declining populations.

Jonathan Berlingeri, Cornell University.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)

Beneficial Insects in New York State Industrial Hemp

Big-eyed bug, Gercoris spp.

Big-eyed bugs are generalist predators that consume a wide variety of small prey including mites, aphids, and small caterpillars. These beneficial bugs can be found in and many vegetable and field crops. Natural populations of Big-eyed bugs can be conserved by eliminating the use of broad-spectrum insecticides and providing shelter and food. The lack of broad-spectrum insecticides labeling in NYS hemp will likely allow Big-eyed bugs to play a role in biocontrol of some potentially severely damaging pests. Big-eyed bugs will feed on many lepidopteran pests in their early life stages. Geocoris punctipes, a species of Big-eyed bug native to NY has been particularly effective against CEW (Lingren et al., 1968). Big-eyed bugs are also an effective biocontrol of several greenhouse pests including aphids and white flies. Management practices described in Michigan State University’s guide to native plants and ecosystem services and in ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping can aid in encouraging Big-eyed bug populations to develop in your hemp fields.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Damsel bug, Nabis spp.

Damsel bugs are generalist predators that consume a wide variety of soft-bodied prey including insect eggs, caterpillars, mites, and aphids. These beneficial bugs can be found in many vegetable and field crops. Natural populations of Damsel bugs can be conserved by eliminating the use of broad-spectrum insecticides and providing shelter and food. The lack of broad-spectrum insecticides labeling in NYS hemp will likely allow Damsel bugs to play a role in biocontrol of some potentially damaging pests. Damsel bugs will feed on tarnish plant bug, aphids and thrips in their early life stages. Management practices described in Michigan State University’s guide to native plants and ecosystem services and in ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping can aid in encouraging Damsel bug populations to develop in your hemp fields.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Syrphidae (Bee Mimics)

Syrphid flies also known as hover flies, or bee mimics, are a family of flies that mimic the warning colorations of bees, wasps, and yellow jackets. The larvae of some syrphids are voracious predators and consume a large number of soft-bodied prey such as aphids, leafhoppers, thrips, and small caterpillars. The larvae will travel along plant surfaces looking for prey. When they contact the prey, they seize it, consume it, and then discard the prey’s exoskeleton. Management practices described in Michigan State University’s guide to native plants and ecosystem services and in ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping can aid in encouraging Syriphid fly populations to develop in your hemp fields.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Convergent Lady Beetle, Hippodamia convergens L.

The Convergent Lady Beetle (CLB) is one of the most common lady beetle species in North America. Convergent Lady beetles are voracious predators and consume large numbers of insect eggs, aphids, scales, thrips, and thrips among other soft-bodied pests. Convergent lady beetles can be used in inundative or innoculative releases to control some soft-bodied pests. Convergent lady beetles are perhaps the poster child of biocontrol and have historically been used in a non-efficient manner. Other options may better suit the needs of a particular farm as CLB have a propensity to disperse upon release. Convergent lady beetles have been effective in the greenhouse setting to control white fly infestations. Convergent Lady Beetles are commercially available from ipmlabs.com.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Minute Pirate Bug, Orius insidiosus

Minute pirate bug (MPB) adults are very small (3 mm long), somewhat oval in shape with a black body, and have white patches on wings that extend beyond the tip of the body. The nymphs are fast-moving small and wingless insects with yellow-orange to brown coloration and have a teardrop shape. MPBs are a generalist predator of a wide variety of small soft-bodied prey including mites, thirps, and aphids. MPB adults and nymphs will feed voraciously on spider mites, white flies, scale insects, and are effective in the greenhouse setting. MPB is commercially available at Koppert Biological Systems.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Green Lacewings, Chrysoperla rufilabris L.

Green Lacewings are commonly found throughout North America and are native to NYS. The larvae are active predators and feed on a variety of soft-bodied insects including aphids, spider mites (especially red mites), thrips, whiteflies, eggs of leafhoppers, moths, leafminers, and small caterpillars. Green lacewings are very effective against aphids and are commonly referred to as aphid lions. Each green lacewing can consume up to 600 hundred aphids per day. C. rufilabris is commercially available at ipmlabs.com.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)Brown Lacewings, Hemerobius spp.

Brown Lacewings are commonly found throughout North America and are native to NYS. Brown lacewings are generalist predators and are voracious as both larvae and adults. Prey include aphids, adelgids, and many other small soft-bodied insects. Brown Lacewings are not commercially available. The management practices described in Michigan State University’s guide to native plants and ecosystem services and ATTRA’s guide to farmscaping can aid in encouraging Brown lacewing populations in your hemp fields.

(Click on images to view them full-size.)References

- Antwi, F. B., & Reddy, G. V. P. (2016). Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Nematodes and Sprayable Polymer Gel Against Crucifer Flea Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on Canola. Journal of Economic Entomology, 109(4), 1706–1712. doi: 10.1093/jee/tow140

- Corn Earworm. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/veg/corn_earworm.htm.

- Crenshaw, W. (n.d.). Fact Sheet: Thirps. Retrieved January 1, 2020, from https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/hempinsects/PDFs/Thrips with photos.pdf

- Crenshaw, W. (n.d.). Fact Sheet: European corn borer. Retrieved January 1, 2020, from https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/hempinsects/PDFs/European%20corn%20borer%20with%20photos.pdf

- Crenshaw, W. (n.d.). Fact Sheet: Lygus bug. Retrieved January 1, 2020, from https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/hempinsects/PDFs/Lygus%20Bugs%20with%20photos.pdf

- Crenshaw, W., Schreiner, M., Britt, K., Kuhar, T. P., Mcpartland, J., & Grant, J. (2019). Developing Insect Pest Management Systems for Hemp in the United States: A Work in Progress. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 10(1). doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmz023

- Fact Sheet: Japanese Beetle. (n.d.). Retrieved December 27, 2019, from http://ccenassau.org/resources/-japanese-beetles.

- Fact Sheet: The Economic Challenge Posed by Declining Pollinator Populations. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/06/20/fact-sheet-economic-challenge-posed-declining-pollinator-populations.

- Farmscaping to Enhance Biological Control: ATTRA: Sustainable Agriculture Program. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://attra.ncat.org/product/farmscaping-to-enhance-biological-control/.

- Flicker, N. R., Poveda, K., & Grab, H. (2019). The Bee Community of Cannabis sativa and Corresponding Effects of Landscape Composition. Environmental Entomology. doi: 10.1093/ee/nvz141

- Haan, N. (2019, August 12). Retrieved from https://www.canr.msu.edu/nativeplants/.

- Hines R. L. & Hutchison W. D (2015, June 9). Flea Beetles. Retrieved from https://www.vegedge.umn.edu/pest-profiles/pests/flea-beetles.

- Hooks, C., Johnson, V., & Leslie, A. (n.d.). Big‐Eyed Bug: A MVP of Generalist Natural Enemies. Retrieved March 1, 2020, from https://extension.umd.edu/sites/extension.umd.edu/files/_docs/programs/mdvegetables/Geocoris.pdf

- Ivy, A. (2010). Japanese Beetle. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://s3.amazonaws.com/assets.cce.cornell.edu/attachments/15633/Gardening-FactSheet-japanese-beetles-5-10-137yxui.pdf?1464059917.

- P. D. Lingren, R. L. Ridgway, S. L. Jones, Consumption by Several Common Arthropod Predators of Eggs and Larvae of Two Heliothis Species That Attack Cotton, Annals of the Entomological Society of America, Volume 61, Issue 3, 15 May 1968, Pages 613–618. doi: 10.1093/aesa/61.3.613

- New York State Pollinator Plan – New York State Department … (n.d.). Retrieved January 1, 2020, from https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/administration_pdf/nyspollinatorplan.pdf.

- Ramirez, R., & Patterson, R. (2011, November). Beneficial True Bugs: Big-Eyed Bugs. Retrieved March 3, 2020, from https://utahpests.usu.edu/uppdl/files-ou/factsheet/big-eyed-bugs.pdf

- Seaman, A., Hoffmann, M., & Woodsen, M. (2018). Demonstrate to growers and consultants how to effectively use Trichogramma ostriniae to biologically control European corn borer in fresh market sweet corn. Retrieved January 10, 2020, from https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/46236/2001erb-NYSIPM.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Vegetable IPM Practices. (n.d.). Retrieved January 3, 2020, from https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/vegetables/vegetable-ipm-practices/.

- Winslow, W. T., Weeden, C. R., & Shelton, A. M. (n.d.). Tarnished Plant Bug. Retrieved January 10, 2020, from http://web.entomology.cornell.edu/shelton/veg-insects-ne/pests/tpb.html.

Links

- https://academic.oup.com/ee/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ee/nvz141/5634339

- https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/06/20/fact-sheet-economic-challenge-posed-declining-pollinator-populations

- https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/administration_pdf/nyspollinatorplan.pdf

- https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/hempinsects/PDFs/Thrips%20with%20photos.pdf

- http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/veg/corn_earworm.htm

- https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/10/1/26/5555744

- https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/hempinsects/PDFs/European%20corn%20borer%20with%20photos.pdf

- https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/46236/2001erb-NYSIPM.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/43304

- https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/hempinsects/PDFs/Lygus%20Bugs%20with%20photos.pdf

- https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/vegetables/vegetable-ipm-practices/chapter-13/section-13-6-7/

- http://web.entomology.cornell.edu/shelton/veg-insects-ne/pests/tpb.html

- http://ccenassau.org/resources/-japanese-beetles

- https://s3.amazonaws.com/assets.cce.cornell.edu/attachments/15633/Gardening-FactSheet-japanese-beetles-5-10-137yxui.pdf?1464059917

- https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/vegetables/vegetable-ipm-practices/chapter-26/section-26-6-2/

- https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/vegetables/vegetable-ipm-practices/chapter-15/section-15-6-2/

- https://www.vegedge.umn.edu/pest-profiles/pests/flea-beetles

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27329629

- https://www.canr.msu.edu/nativeplants/

- https://attra.ncat.org/product/farmscaping-to-enhance-biological-control/

- https://utahpests.usu.edu/uppdl/files-ou/factsheet/big-eyed-bugs.pdf

- https://extension.umd.edu/sites/extension.umd.edu/files/_docs/programs/mdvegetables/Geocoris.pdf

- https://academic.oup.com/jee/article-abstract/72/1/97/2212835

Contact

Elson Shields

Professor, Entomology

4144 Comstock Hall (this address is subject to change)

es28@cornell.edu

+1 (607) 255- 8428